Prevalent ‘eternal chemicals’ could be harming our livers, study finds

New research shows that per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, known as PFAS can damage people’s livers over time. The study, a review of evidence in rodents and humans, may also show that exposure to PFAS may contribute to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, a chronic metabolic disease that has become more common.

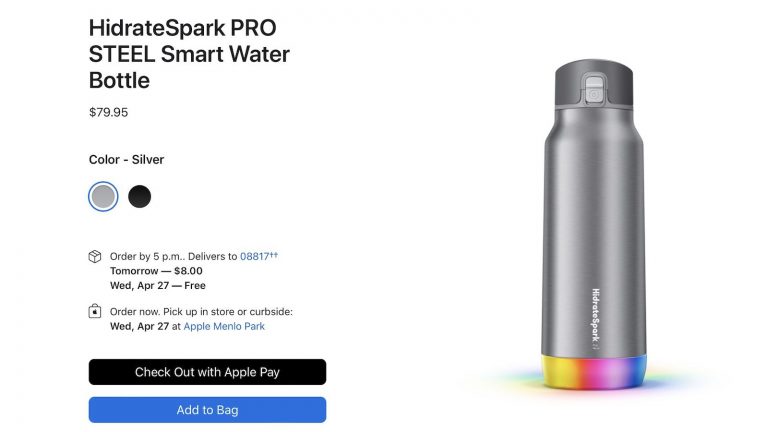

PFAS are often synthetic chemicals used in manufacturing, especially in plastic products or cosmetics. But because PFAS don’t break down easily, they ended up pretty much everywhere in the environment, earning them the sinister moniker Chemicals Forever. This ubiquity also extends to living things, with many people and wildlife having detectable levels of PFAS in their bodies at some point.

These chemicals are not harmless. They are known to mimic or otherwise disrupt the body’s hormones, which can increase the risk of various health issues, including cancer and infertility. This new research published Wednesday in Environmental Health Perspectives suggests that the liver is not spared from the effects of PFAS.

Researchers, based at the University of Southern California, reviewed data from more than 100 studies involving rodents or humans. Overall, they found a link between higher levels of PFAS in the body and higher levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), an enzyme produced by the liver. This is a concerning link, as high levels of ALT in the blood are a common sign of liver damage.

“The main takeaway from this review is the comprehensive evidence across animal, population-based, and occupational studies that exposure to PFAS is linked to liver injury,” said lead author Sarah Rock, a doctoral student in the Department of Science. of population and public health at the Keck School of USC. of Medicine, Gizmodo said in an email. “These findings contribute to the growing evidence that PFAS may play a role in the development of several diseases.”

In animals, Rock and his team also found a clear link between greater exposure to PFAS and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which is characterized by an accumulation of fat in the liver that is not caused by chronic alcohol consumption. NAFLD often causes no symptoms on its own, although people may experience fatigue and abdominal pain. Sometimes, however, the accumulation of fat can cause inflammation of the disease, a condition called non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). People with NASH are then more likely to develop serious complications such as permanent scarring, internal bleeding and complete liver failure.

NAFLD and NASH rates have steadily increased in the United States and around the world. recent commentsalongside rates of important risk factors for NAFLD such as obesity and type 2 diabetes (in the United States, a quarter of adults are valued To see her). The latest findings may show that chronic exposure to PFAS played some role in this increase, but studying NAFLD has been difficult and expensive, the authors say. So far, there has been little research in humans that has attempted to determine if PFAS may be a contributing factor. That said, higher ALT levels in people can also be a sign of fatty liver disease, and other studies have found a link between PFAS and other possible biomarkers, such as high cholesterol.

Another limitation in studying the negative health effects of PFAS chemicals in general is that there are many such chemicals and people are exposed to them in different ways. It is therefore difficult to determine which ones harm us and how they enter our body. In this review, the team isolated three specific PFAS – perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), and perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) – as being associated with signs of liver damage.

Researchers say that more studies will be needed to isolate the complex nature of PFAS exposure to the liver. But at the very least, they add, their findings show that these chemicals are a potential health threat and that more needs to be done about them – a feeling on which many scientists agree.

“The evidence from this liver injury study, the researchers alongside the work of many others looking at PFAS exposure and other disease outcomes, suggests that we should be doing more not just to phase out the use of PFAS, but also to actively eliminate it from our environment,” Rock mentioned.

#Prevalent #eternal #chemicals #harming #livers #study #finds