Texas stumbles in efforts to punish green financial firms

Fossil fuels power the Texas economy, accounting for about 14% of the state’s gross product between 2019 and 2020. Today, Texas is the first state in the nation to pass anti-fossil fuel divestment laws.

For years, fossil fuel-producing states have seen investors turn away from the companies that are causing the climate crisis. Last year, one state decided to push back.

Texas passed a law treating financial companies that avoid fossil fuels the same way it treated companies doing business with Iran or Sudan: boycott them.

“This bill has sent a strong message to Washington and Wall Street that if you boycott Texas energy, then Texas will boycott you,” Texas Rep. Phil King said from the floor of the Legislature. of Texas during deliberations on the bill, SB 13, last year. .

But the Lone Star State is trying hard to enforce the law. Loopholes and exceptions written into the law could undermine its impact on financial firms that have aggressive climate policies.

Last March, the Texas state comptroller began sending letters to financial institutions, probing their climate policies. Leslie Samuelrich, president of Green Century Capital Management, a fossil fuel-free mutual fund, said her company recently received her letter.

“It was very politically motivated,” she says. Samuelrich says she plans to skip the one she got.

Even so, Samuelrich says the law could have a “chilling effect” on some investment firms.

Despite emerging problems in Texas implementing the first law penalizing corporations for fossil fuel divestment, the concept of a green finance boycott is spreading. At least seven other states are considering or have passed similar legislation, raising the possibility that a coalition of fossil-fuel-producing states may put pressure on Wall Street.

“The state of Texas is a big state with big money,” says Rob Greer, associate professor at the Bush School of Government and Public Service at Texas A&M University. “They can definitely kind of make a difference. But when you’re talking about the biggest financial institutions…global trends are going to be the ones that dictate a lot – and the state of Texas may be out of step with some of those global trends. ”

A popularity contest

Fossil fuels help power Texas’ economy, employing about 14% of Texas workers in 2019, according to the American Petroleum Institute. They also fuel state policy. The new law was drafted by Jason Isaac, a former lawmaker whose foundation gets money from the fossil fuel industry.

The law prohibits Texas state pension and investment funds from doing business with companies that the state comptroller says “boycott” fossil fuels. The funds are worth about $330 billion, though it’s unclear how many of them are invested in companies Texas plans to boycott. The law applies to new or existing contracts over $100,000.

Texas applies the term “boycott” liberally. Because of the way the law is written, even companies that invest their customers’ money in fossil fuels but also offer non-fossil fuel financial products could be considered boycotters.

Vehicles drive along Congress Avenue which leads to the Texas Capitol building in Austin. Last August, Texas hired MSCI, a financial ratings firm that analyzes green investments, to help it compile a list of companies it should boycott, according to public records obtained by Floodlight.

nce Texas passed its bill, at least seven other states have considered or passed similar legislation. Last fall, a coalition of 15 mostly Republican-led state treasurers issued a letter saying they would stop doing business with financial institutions engaged in fossil fuel “boycotts.”

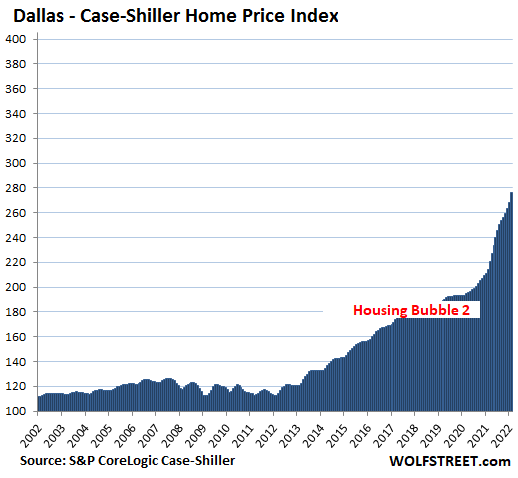

But if state boycotts are spreading, so is the popularity of green investments. In 2014, some $52 billion was divested from fossil fuels worldwide, according to the Global Fossil Fuel Divestment Commitment Database. In 2022, that figure was $40.43 trillion.

Experts are skeptical of the Texas law’s chances of success. They point to gaping gaps in the legislation. They say the climate risks to the financial system are so huge that there is no real way to stop financial firms from assessing them – and becoming greener in the process.

“I see this as the next or one of many token actions,” says David Spence, a law professor at the University of Texas at Austin.

New documents obtained by investigative reporting group Floodlight reveal just how difficult the Lone Star State has been figuring out who to quit working with.

The controller’s dilemma

When the Texas state legislature initially debated its fossil fuel boycott bill, representatives from the state comptroller’s office pointed to an obvious problem: no one had ever compiled a list of companies like this before.

“It’s not easy, you’re really going to have to do a lot of research,” says Sheri Greenberg, a former Democratic Texas state legislator who helped oversee pension fund investments.

Texas is now learning how difficult it is to determine which financial firms are actually going green. There are no national standards for companies to report their greenhouse gas emissions.

A spokesperson for the comptroller’s office said the process “proved difficult”.

This spring, however, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission announced it would begin standardizing how financial companies must disclose climate change risks and opportunities.

But for now, figuring out who is really doing climate-friendly finance is actually quite tricky. So tricky, in fact, that the new law could even trap consultants the state has hired to help.

Last fall, Texas hired MSCI Inc., a financial ratings firm that analyzes green investments, to provide data on financial firms, public records obtained by Floodlight show.

But there was a problem: MSCI is exactly the kind of company the Texas authorities are looking to boycott: it has committed to carbon neutrality by 2040.

Floodwaters cover an access road to oil refineries in Port Arthur, Texas, in the aftermath of Hurricane Rita in 2005.

t’s the kind of thing that can get you in trouble in Texas right now. In emails, a lawyer for the comptroller’s office expressed concern that the state would not be allowed to work with MSCI under the new law.

The lawyer’s solution was to keep the contract cheap – below the amount at which the new law comes into effect. After email negotiations on Aug. 26, MSCI agreed to drop its price from $100,000 to $95,000, according to the emails. The contract creaked under the bar set by the new law, and was signed.

“The simple truth is that creating this list would present no challenge if these companies were open, transparent and honest about their position on the fossil fuel sector,” a spokesperson for the comptroller’s office wrote in a statement.

But the problem with MSCI’s contract is only the first hurdle the state can expect as it tries to stem the tide of climate-conscious investment.

Loopholes and Exclusions

Because of how Texas has defined the term “boycott” in law, financial companies that simply invest in other funds that avoid fossil fuels could potentially be breaking the law.

“Take Wells Fargo, for example,” says Greenberg, the former overseer of state pensions. “If they have mutual funds or exchange-traded funds in their portfolios that prohibit or limit fossil fuel investments, then that’s problematic.” But the law also contains a myriad of exclusions. For example, companies that want to work with Texas can still avoid investing in fossil fuels as long as they do so for strictly financial rather than ethical or environmental reasons.

“It’s smart business not to invest in fossil fuels,” says Robert Schuwerk, executive director of the North American office of Carbon Tracker, a financial think tank that studies the green energy transition.

If a company believes that its fossil fuel assets are going to be worth less in the future due to factors such as carbon taxes or more powerful natural disasters caused by climate change, it makes sense for a company to sell those assets now, says Schuwerk. .

The Texas Comptroller’s Office did not comment on the effect of the exemptions in the law. A spokesperson for the office asked the legislature about these exceptions.

“We don’t know what the impact on business behavior will be and we don’t want to speculate on how businesses will respond,” the spokesperson said.

Other states that have passed similar laws argue that allowing certain exceptions will not weaken the effort.

“If they’re making a business decision,” says Riley Moore, the West Virginia state treasurer, “somebody asks a coal company for a loan, and they decide it’s a big credit risk, and they don’t want to do it, so that’s fine.”

Moore says he sees the law applying directly to public statements by companies.

“(If) they say that we as a financial institution will not lend money to coal, for example. That’s a general statement that poses a problem for the state of West Virginia,” said Moore.

Samuelrich, the mutual fund manager, says that for his company, being listed as a boycotted entity may not be such a bad thing.

“I don’t think it’s going to affect demand at all,” she said. “In fact, it might make more people realize that they can invest without fossil fuels.”

This story is a collaboration with Projector, a non-profit environmental news organization.

#Texas #stumbles #efforts #punish #green #financial #firms